In the previous post we took a look at the Amazon/Hachette dispute, and did so in a way that sought

to add context to a feud in which one party was often characterized as the ‘good

guy’ and the other as the ‘bad guy'. As with most things, it’s more complex than that, particularly as the book publishing industry attempts to steady itself on the choppy waters of the shift from physical to digital products and services.

As hard copy print declines in popularity and eBook sales rise, the profit margins of publishers also stand to slide. When you’re not in the business of making, shipping, and selling things that occupy physical space in boxes, warehouses, and stores, it’s a whole different game. The pricing model of the legacy system looks something like this:

A new hardcover book now usually retails for $27.99. The pie

chart below provides a rough guide to how those dollars are divided up between

publisher, retailer, author, and agent. Not all authors have agents, but

authors dealing with the major publishing houses generally do and for their

services agents receive 15% of the author’s royalty rate. Note that these are not carved in stone

numbers, but according to a source in the publishing industry, who I ran them

past, they’re accurate, give or take a percent here or there.

It always helps to add some notes to such numbers, so here

we go:

Note that absent from this breakdown are fees paid to

designers, printers, wholesalers, warehousers, shippers, and publishing house staff. Those costs tend

to come out of the publisher’s piece of the pie and when added up leave the

publisher with about 10 - 12%.

Note that absent from this breakdown are fees paid to

designers, printers, wholesalers, warehousers, shippers, and publishing house staff. Those costs tend

to come out of the publisher’s piece of the pie and when added up leave the

publisher with about 10 - 12%.

And then there’s the bookseller/retailer, who appears to be

helping him/herself to an oversized slice, but rest assured, overhead in retail

is high – leases, staff, equipment, advertising, etc. (Ask yourself: when was the last time you met

a wealthy bookstore owner...meaning one that became wealthy from selling books, not dabbling in retail for fun or philanthropic purposes).

Also note that the 10% paid to the author (minus 15% to the

agent) is paid after the advance – the money the publisher paid the author

before the book was actually written -- is paid back to the publisher.

And finally, to cap off our notes section, it’s worth

mentioning that the dollar pie, as split above, does not include any rights the

author and/or agent have retained for licensing merchandise, foreign markets,

or dramatic use (e.g. film adaptation).

After this post went up last night I heard from a friend who is a veteran of the New York and Boston publishing industry (who preferred to remain anonymous) and he added the following way of looking at the flow of dollars, so I'm sharing those notes with you here.

Using the same suggested list price of $27.99 for a book the numbers can be broken down this way:

The book is sold by the book publisher to the bookseller, or retailer, at a 'discount' of 50%. In other words, the publishing company gets $13.50 of revenue and the retailer then prices the book for sale in his/her store at a level at which costs can be covered and (hopefully) some profit margin can be obtained. Of the $13.50 now in the book publisher's pocket the dollars are divided as follows:

After this post went up last night I heard from a friend who is a veteran of the New York and Boston publishing industry (who preferred to remain anonymous) and he added the following way of looking at the flow of dollars, so I'm sharing those notes with you here.

Using the same suggested list price of $27.99 for a book the numbers can be broken down this way:

The book is sold by the book publisher to the bookseller, or retailer, at a 'discount' of 50%. In other words, the publishing company gets $13.50 of revenue and the retailer then prices the book for sale in his/her store at a level at which costs can be covered and (hopefully) some profit margin can be obtained. Of the $13.50 now in the book publisher's pocket the dollars are divided as follows:

So, working with these numbers we have about $2.50 going to the author and about $0.50 to the agent, per book sold. Again, these payments would be after any advances made to the author have been recovered from actual sales of actual books. Until such time the book publisher is fronting all the cash. Of the approximately $10 the book publisher now has in cash flow, project expenses are paid (copy editing, book design, proofing, printing, shipping, etc) as well as overhead (rent, staff, equipment, insurance, the electricity bill, any Keurig pods in the kitchen, etc).

Is that everything? Not quite. The books the publisher sells to the retailer aren't really sold. They're consigned. Meaning that depending on the deal struck, the retailer can return unsold inventory to the publisher, in which case the publisher will be issuing a refund to the retailer.

The other things that can happen:

- The books that didn't sell at full price remain in the store, but move from the nice neighborhood, i.e. the window display or attractive tables at the front of the store, to the grab bag that is the remainder table, where they're usually priced between two and ten dollars.

-The books get sold by the retailer to an overstock company, such as a discount store (Marshall's, Winners) or dollar store.

- The books get 'pulped', or destroyed, which in the past probably meant landfill and today means shredded and recycled.

Now that we have two sets of data on the dollars, albeit with some variation, we can agree on this: the pie charts above shows us the book industry as it’s been for the past several decades. Like the rest of the creative industries, where outcomes are impossible to know until they actually happen, it’s a high risk/high reward system. Major book publishers, not unlike music labels and movie studios, have to put up capital in the hope that they will turn a profit, even though in all of these industries the general rule of thumb is that about 95% of projects taken on do not break even. If anyone really knew anything would JK Rowling’s manuscript for Harry Potter have been rejected 12 times? And would Penny “Laverne” Marshall have received a hefty $800,000 advance for her memoir, which ended up selling 17,000 copies. Using our newly acquired skills in book industry math, that level of sales constitutes a small fraction of what the publisher would need just to get back to $0.

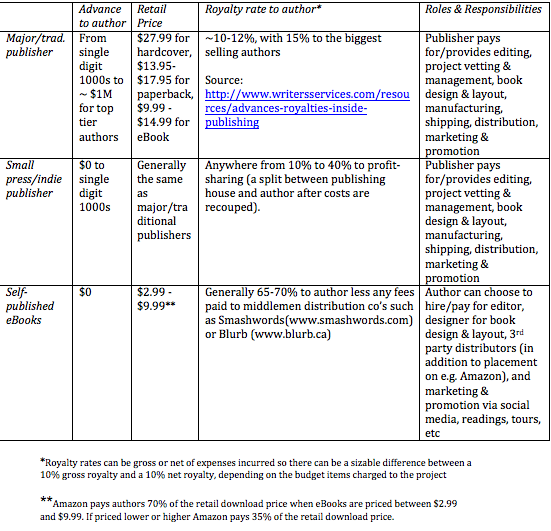

The next question in our analysis: how do these numbers change when we look at small press or indie publishers? Or when we consider the new possibilities in the publishing marketplace, such as bypassing hard copy altogether and going the route of the self-published eBook? There's a chart for that -- primarily because I whipped one up -- and here it is:

|

| Click to enlarge |

And a few notes regarding these numbers:

The number of copies to break even can be a few hundred for

a self-published eBook (no advance to repay), approximately 1500 to a few thousand for an indie press

book (advance of zero to a few thousand), and ten thousand plus for a title with a major publishing company (assuming an advance in the low tens of thousands).

On average -- and

averages in cases such as these can be charitable, because they also include the numbers at the

top end -- this is what sales figures look like:

The average book published sells 250 copies per year and

3,000 copies over its lifetime. In other words, it loses money. And even at

that level we’re talking about the top 10% of all books published. 90% of books

published sell fewer than 100 copies per year. For eBooks, average sales are estimated to be 100-150. And that's total lifetime sales, though admittedly we're still in the early days. And while the major eBook retailers (Barnes &

Noble, Amazon) do not publish statistics on eBook sales (whereas they do for

print books), this conscientious blogger ran the numbers

forensically and came up with a figure of $297 for the average eBook royalty

paid to authors in 2013.

Which brings us to the grand finale of this post on books

and bucks. When we take the whole picture into account – let’s use the

approximately 1 million books published each year in the U.S. because it’s an

easy landscape to work with and it's the world's largest book market – this is how the dollars shake out:

With a single digit percentage of authors published by major houses making something resembling a barebones living wage ($40,000 or more), and the biggest proportion of authors being those that self publish. Though the chart below shows this group as earning $1 - $4,999 per year, I think that after taking into account the other numbers in this post it’s safe to assume that the actual dollars in pocket come closer to covering the cost of a take-out meal, as opposed to, say, a really nice couch. (Source: Digital Book World 2014 report)

With a single digit percentage of authors published by major houses making something resembling a barebones living wage ($40,000 or more), and the biggest proportion of authors being those that self publish. Though the chart below shows this group as earning $1 - $4,999 per year, I think that after taking into account the other numbers in this post it’s safe to assume that the actual dollars in pocket come closer to covering the cost of a take-out meal, as opposed to, say, a really nice couch. (Source: Digital Book World 2014 report)

So there you have it for the basics of the book industry numbers. Remarkably similar to the music industry, as examined in detail on this blog last year.

In Part 3 of this post we take a look at the size of the overall eBook market, which will set the stage for Part 4, when we’ll go beyond the big publishers and big retailers, and look at some of the new players in the publishing industry as it transitions from a high barrier to entry hard copy based business to a low barrier to entry digital one. Is it meet the new boss, same as the old boss? Or are we better off than we were in the world of a handful of gatekeepers, many aspirants, and a relative few selected for a promenade in the marketplace?

Oh, and there's even a Part 5, in which we take a closer look at case of the initially self-published 50 Shades of Grey, and how its author, E.L. James became the world's top earning author just a couple of years after she first tried her hand at writing.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete